Execution Ceremony

Several years ago an end-piece in New Scientist magazine asked that timeless question, “How long is one aware after being beheaded?”

Among the reader comments was this bit of grotesquery, so vivid it borders on the poetic:

Dr Livingstone wrote that Africans he encountered were aware that consciousness is not lost immediately. He recounts how they bent a springy sapling and tied cords from it under the ears of a man to be decapitated so that his last few moments of awareness would be of flying through the air.

John Rudge, Harlington, Middlesex

Holy cow! Could this possibly be true? After a bit of research I have to conclude that the ceremony described actually did happen—though I found no evidence that Dr. Livingstone reported this, nor that the victim was assumed to be aware of his final “journey” towards the heavens. More than likely Mr. Rudge had conflated scenes from descriptions given in modern biographies of Henry Morton Stanley (not David Livingstone.)

The first public descriptions of this style of execution come from the ethnologist Walter Hough:

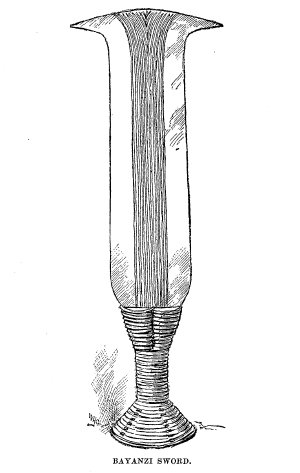

A Bayanzi execution

In executing, the condemned is made to sit down on a block just behind a post, his limbs passing on each side of it. The post reaches to the height of his chin. His arms, legs, and body are tied to stakes. A strong sapling is bent down, having at its extremity a collar suspended by cords. This collar is placed around the victim’s neck, producing so great tension, that, when the executioner delivers the blow, the severed head is thrown into the air with the force of a bomb.

The circumstance which forms the subject of this paper was witnessed in November, 1884, at Loukolela, by Mr. E. J. Glave. […] So far as known by the writer, this is the first time that an account of the Bayanzi or a similar execution has ever been published. (From a letter dated June 9th 1887.)

Science, Vol. 9, No. 229. (Jun. 24, 1887)

And again, a few months later, Hough writes:

Notes on the Ethnology of the Congo

It is really in bad taste to describe an execution, but life there is so cheap and the Congo- African way of relieving a man of his head so unique that it will bear description. In order to give an éclat suitable to African taste, and to render the feat of decapitating with the weapon possible, the victim is secured to a seat and a strong sapling bent down and fastened by means of cords and a collar around his neck; then, while his neck is taut the high executioner delivers the blow, and the severed head is thrown into the air like a bomb.

The American Naturalist, Vol. 21, No. 8. (Aug., 1887)

E. J. Glave, mentioned by Hough above, did not write publicly about these events until an April, 1890 article for Century Magazine. Glave,who was only 18-years old at the time, was an adventure seeker who had been left in charge of the Loukolela camp by Stanley himself on his journey up the Congo River. Glave writes:

Slave Trade in the Gongo Basin

A Pole is now planted about ten feet in front of the victim, from the top of which is suspended, by a number of strings, a bamboo ring. The pole is bent over like a fishing-rod, and the ring fastened round the slaves neck, which is kept rigid and stiff by the tension.

An unearthly silence succeeds. The executioner wears a cap composed of black cocks feathers; his face and neck are blackened with charcoal, except the eyes, the lids of which are painted with white chalk. The hands and arms to the elbow, and feet and legs to the knee, are also blackened. His legs are adorned profusely with broad metal anklets, and around his waist are strung wild-cat skins. As he performs a wild dance around his victim, every now and then making a feint with his knife, a murmur of admiration arises from the assembled crowd. He then approaches and makes a thin chalk mark on the neck of the fated man. After two or three passes of his knife,.to get the right swing, he delivers the fatal blow, and with one stroke of his keen-edged weapon severs the head from the body. The sight of blood brings to a climax the frenzy of the natives: some of them savagely puncture the quivering trunk with their spears, others hack at it with their knives, while the remainder engage in a ghastly struggle for the possession of the head, which has been jerked into the air by the released tension of the sapling. As each man obtains the trophy, and is pursued by the drunken rabble, the hideous tumult becomes deafening; they smear one anothers faces with blood, and fights always spring tip as a result, when knives and spears are freely used.

The Century Magazine, Volume 39, Issue 6. (Apr. 1890)

Herbert Ward, a companion of Stanley, wrote a description for Scribner’s Magazine several months earlier. It is unclear if Ward actually witness these events, but the text is so similar to Glave’s (who is shown to have been a witness in 1884 by Hough above) one can only assume Ward had been given access to Glave’s notes or his letters to contemporaries (perhaps Stanley himself.)

Life Among the Congo Savages

The victim is placed on a block of wood, with his legs stretched out stiff in front of him. Beside each ankle a small stake is driven firmly into the ground, the same at the knees and at the sides, running up under the arm-pits. These are then firmly bound together by cords, securing the body rigidly in its position. His head is then placed in a kind of cage formed by a ring of cane fastened round the neck with numerous strings attached to it which are drawn up over the head and tied together in a loop. A pliant young sapling is now stuck in the ground about twelve feet from the victim and bent over toward him until the extreme end is caught in the loop, and all the strings round the ring are drawn taut and the neck stretched stiff by the strain.

The executioner then makes his appearance, escorted by the young men and women of the village, each holding over him a palm-leaf, forming a kind of canopy. On reaching the victim they fall back and leave him there alone. He wears a cap formed of large black cock’s tails; his face is blackened with charcoal down to the neck; his hands and arms are also blackened up to the elbows, and the same with his legs down to the knees. Around his loins he wears several wildcat skins. Standing in front of his victim, he makes at first two or three feints with his knife, to get a proper swing. Then, deliberately bending down and taking a piece of chalk, put there for the purpose, he draws a thin line around the neck, and putting a little fine sand on his hand so as to get a good grip, with one quick blow with his knife, severs the head from the trunk. Until just before the execution the whole village is wild in expectation of the event. Groups of dancers are to be seen, drummers at work, and every kind of musical instrument to add to the tumult. The head, after being severed, is jerked up in the air by the released tension of the pole.

Scribner’s Magazine, Volume 7, Issue 2. (February 1890)

In a biography of Stanley, “The Man Who Presumed”, (1957) the author, Byron Farwell, describes this same execution technique though this time witnessed by yet a third acquaintance of Stanley, Lieutenant Alphonse Vangele, at the Equator station, near to Glave’s camp.

In the same passage Farwell relates another anecdote of Herbert Ward (mentioned above):

Herbert Ward, another of Stanley’s officers, recorded seeing a similar ceremony. Just before one of the slaves was to be decapitated, however, a relative of the dead chief came up to the doomed slave and gave his a message to relay to the spirit of the departed. He concluded his message with: “… and tell him when you meet, that his biggest war canoe, which I inherit, is rotten.”

Ward himself had written about this event in his book A Voice from the Congo (1910), p. 162.

So, finally what does this say about the comment from Mr. Rudge of Harlington, Middlesex? It seems clear to me that he got the core of the story correct, just accidentally confused Livingstone with Stanley. And that dark bit of poetry about the victim’s “last few moments of awareness would be of flying through the air” was possibly a conflation of the Ward anecdote to with the more extreme beheading story.