Dropkick Murphy’s at Bellows Farm

While the Dropkick Murphys are a fine group, I’ve always been more interested in the name of the band itself. Members have always told that they took the name from a supposed detox center, owned and operated by a former wrestler by the name of John “Dropkick” Murphy. The Boston Herald columnist Howie Carr has salted his columns with mentions of the place for years— generally in reference to the Kennedys—well before the existence of the band of the same name. E.g.:

“And how would you like to be Joe Kennedy? Here’s your uncle, looking more like an escapee from Dropkick Murphy’s every day, and he says he’s going to run again in 1994? ”

- Howie Carr. Boston Herald. October 28, 1991

So while the name of the place is fairly well-known (around Boston anyway) its actual existence has remained somewhat more legendary.

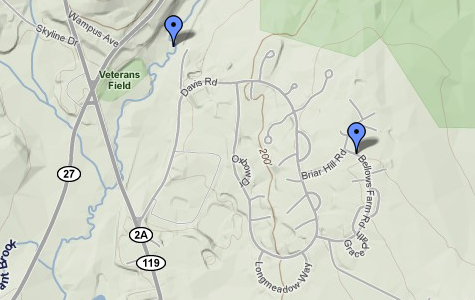

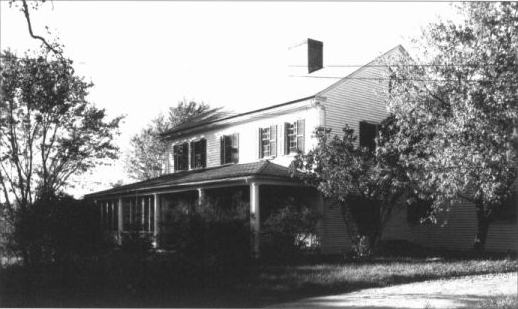

The Bellows Farm Sanitarium aka “Dropkick” Murphy’s. Located at 40 Davis Road in Acton. Originally the Ebenezer Davis house. Since torn down.

Several places mention that its official name was “Bellows Farm” located in Acton, Massachusetts. There is now a road called “Bellows Farm Road” in Acton on or near the original property.

A Massachusetts court case from 1973 (2 years after the facility closed) mentions Murphy:

“This is a bill in equity under G. L. c. 231A, seeking a declaration whether certain amendments to the zoning by-law of the town of Acton (town) apply to a parcel of land (locus) owned by the plaintiffs Bellows Farms, Inc. and John E. Murphy and on which the plaintiff Donald P. O’Grady has contracted to build 402 apartment units. The defendants are the town, its building inspector and the members of its board of selectmen.”

BELLOWS FARMS, INC. & OTHERS vs. BUILDING INSPECTOR OF ACTON & OTHERS. April 4, 1973 - November 7, 1973.

This land is along the Nashoba Brook in Acton which is mentioned in an article on fishing in Massachusetts from the New York Times:

We visited a spot in Boston (Jamaica Pond); then he gave me an hour on Neshoba Brook (on a stretch open to the public and owned by Dropick Murphy, a former wrestler) where I caught two brook trout.

“Wood Field and Stream” New York Times. May 9, 1968.

Finally there is this small advertisement for the facility a year after it opened (the only one I could find anywhere)

The New York Times. July 5, 1942.

$25 per week works out to be about $325 per week in 2009 dollars, which isn’t exactly cheap. Legends of the place being some last stop for end of the line winos might be a bit misplaced.

Dropkick Murphy was an actual wrestler. Here is small clip from back when The New York Times actually used to report on professional wrestling:

The New York Times. Jun 26, 1938.

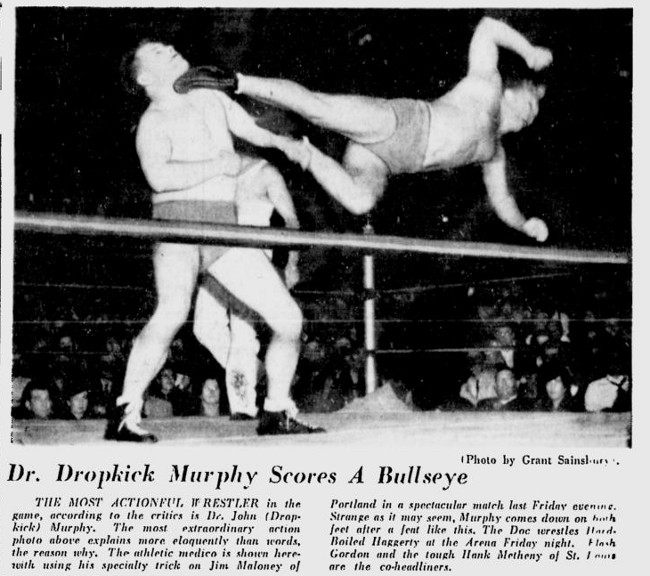

Dropkick Murphy vs. Jim Maloney, September 22, 1939

Metropole

“Kafkaesque” is perhaps our most overused eponymous adjective, but in the case of Hungarian writer Ferenc Karinthy’s brilliant Metropole, there is simply no more fitting term to employ. It’s amazing that this book, written in 1970, has only recently been translated into English for the first time.

Budai, a linguist on a trip to Helsinki for a conference, mistakenly lands in an unknown, crushingly-overcrowded city where people speak an utterly incomprehensible language. Signs, symbols, art, food, religion, all bare a resemblance to a vaguely pan-European culture, but the populous appears to be a mixture of races from all over the world. His frustrations slowly morph into panic then resignation as his inability to communicate drains away his assurance and dignity in the claustrophobic atmosphere amongst the indifferent, if not outright hostile multitudes.

Eventually he begins to wonder if everyone else around him is just as trapped as he is. It’s hard not to see the novel as an allegory of life in the Eastern Bloc. The original title of the book is “Epépé” which is one of the ever-shifting names Budai applies to the single person he manages to maintain the thinnest tendril of a relationship with. The fact that her name shifts seemingly unselfconsciously on Biadu’s part suggests his unknowing abidance at the cusp of some dreamworld. It’s perhaps telling that the Hungarian title focuses more on this one human relationship than the dehumanizing metropolis of the English translation. It hints at the ultimate hope of salvation which is perhaps the most un-Kafkaesque aspect of the entire book.