Baffinland

Greg Easterbrook’s article “Global Warming: Who Loses—and Who Wins?” from the April 2007 Atlantic Monthly discusses geopolitical issues that may arise as world-wide temperatures continue to increase. One statement in particular caught my eye:

For centuries, Europeans drove the indigenous peoples of what is now Canada farther and farther north. In 1993, Canada agreed to grant a degree of independence to the primarily Inuit population of Nunavut, and this large, cold region in the country’s northeast has been mainly self-governing since 1999. The Inuit believe they are ensconced in the one place in this hemisphere that the descendants of Europe will never, ever want. This could turn out to be wrong.

It seems in fact that this is already the case, and has been for time. (See this excellent overview.)

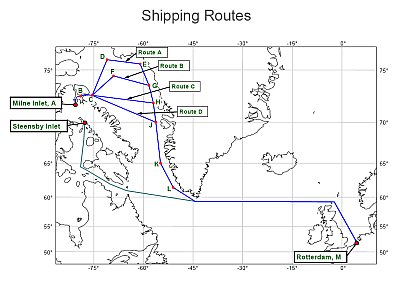

In 2006, the Baffinland Iron Mines Corporation announced plans for a huge iron mine along the Mary River in the northern reaches of Baffin Island. Transporting all of the ore would require the creation of a railroad, a first for the huge island, and the development of a massive new seaport at either Milne Inlet or Steensby Inlet. (See map). The seaports would need to be kept open using ice breakers for much of the year as the ice is often over 2 meters thick. The northern route would take these massive ships right past the new Sirmilik National Park.

The ore of is of such high quality that it can be shipped without any further processing, so the mine wouldn’t be as environmentally damaging as one of this size could be—at least at first.

If this mine comes online, the closest settlement, Pond Inlet, will be in for massive changes. Now that the Inuit are in control of Nunavut, they will at least be in the position to benefit directly from these changes. Still I can’t help feel ambivalence and concern about such a heavy footprint on such sacred ground.